“78% of customers say…” - retail’s dangerous addiction to customer feedback

Waitrose announced today that it will no longer offer free newspapers to customers who are members of its loyalty scheme, replacing them with a more ‘personalised’ offer. The supermarket chain didn’t share why they made this decision but tinkering with loyalty schemes is nothing new. Retailers want to find the configuration of rewards and incentives that will make customers choose them over a rival.

Broken analytics

The way retailers often do this is asking customers what they think. Maybe in the past Waitrose asked customers if the reward of a free paper would make them shop at Waitrose more. Maybe a high percentage of customers agreed that, yes, a free paper would certainly entice them to do that.

We’ve no idea if that’s what Waitrose really did, but it’s a reasonable guess. Retailers are desperate for data; something concrete that will tell them about their relative attractiveness – the reasons shoppers choose them over a competitor. And what they usually do is ask customers.

Customer analytics produces reports riddled with sentences starting “Customers say…” or variations on that, with the resulting stats interpreted as gospel truth.

“Shoppers say incentives like free shipping (75%), simple and/or free returns (60%), and loyalty or rewards programs (56%) all increase their likelihood to buy,” says the Salesforce Connected Shoppers Report, Fourth Edition, 2021, released last November.

In this case, Salesforce asked 1,600 shoppers what they thought and used their responses to come up with handy takeaways like “Loyalty is the new brand differentiator”, or “Millennials and Gen Z value exclusive access to limited products and experiences nearly two times more than Silents and Baby Boomers when it comes to loyalty programs.”

What’s the problem?

Why can’t we ask 1,600 shoppers what they think and get a reliable answer? The problem is customers lie. We don’t do it intentionally, but it’s hard to post-rationalise why we act the way we do when we make a purchase. There are hundreds of cues, mindstates and circumstances which influence how we shop in any given circumstance, and it’s impossible for customers to be aware of them all, let alone accurately report them afterwards. (It’s also impossible to cover them all in a customer survey.)

Psychologist Daniel Kahneman, the founder of behavioural economics, differentiates between the experiencing self and the remembering self. The self that experiences life in the moment is very different to the self who remembers experiences afterwards. “We do not attend to the same things when we think about life, and when we actually live,” Kahneman says.

A key reason our memories are biased and inaccurate, according to Kahneman, is the focusing illusion; we can’t think about a circumstance without distorting its importance.

This cognitive trap is at the heart of the problem with customer analytics. Ask a customer what they think about loyalty programmes, and the importance of loyalty programmes in their memory of how they acted becomes distorted. It’s not possible to get an unbiased answer when we ask a customer their opinion on how they shop, because our brains can’t remember without bias.

The remembering self also can’t accurately predict how it will act in future. “When we think about the future,” Kahneman says, “we don’t think about the future […] as experiences. We think about our future as anticipated memories.”

Ask 1,600 customers what they think, and you can’t rely on what they say. You might get some right answers, some of the time. It’s possible that an attractive loyalty program really is the top reason a shopper chooses one retailer over another.

But you don’t know. Not for sure. Customer opinion is biased. It’s unreliable. It’s often just wrong. But retail execs repeat myths and guesses based on that data, and those guesses become accepted thinking.

Biased data = poor investment decisions

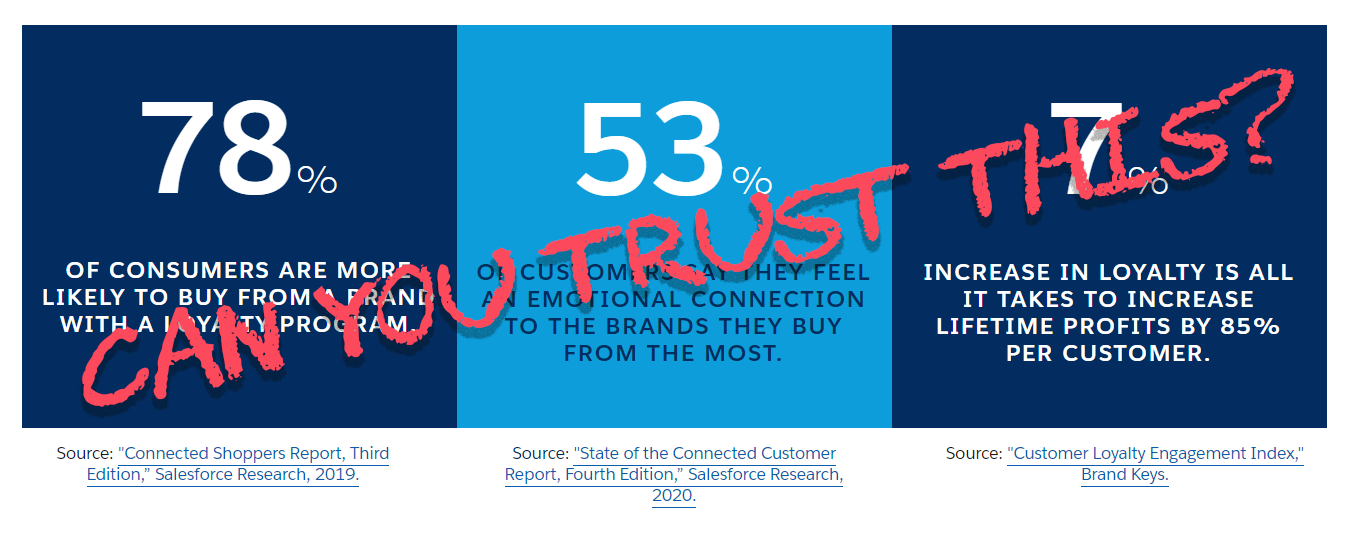

Retailers base major investment decisions on that biased and unreliable data. If 78% of consumers say they love loyalty programmes, retailers obediently pump their CX budget into a loyalty programme.

But what if a loyalty programme is not actually a key reason a customer chooses you, or chooses away from you?

What if there are other hidden variables influencing their choice? Variables the customer isn’t aware of, or that just weren’t included in the multiple-choice survey? In that case, changing the loyalty programme might not result in significantly more customers choosing you. Investing based on that biased data may not deliver ROI.

Experience analytics

Understanding relative attractiveness requires us to fully understand the whole shopping journey that customers go through to spend money with us. It is that shopping journey that must be interrogated, not the customer. A data-driven, unbiased retail analytics must use objective metrics that can be measured without the remembering self getting in the way.

Old-fashioned customer analytics asks customers what they think and relies on their answers being true. The new discipline of experience analytics examines the shopper journey, measuring the many different variables that influence customer decisions at every stage of that journey. It doesn’t attempt to measure opinion; it measures reactions and behaviour.

Customer analytics relies too heavily on the unreliable remembering self. Experience analytics is the new way to access the self that’s in the driving seat when we shop.